Monument Photo by

Dana Stubbs

Monument Photo by

Dana Stubbs

Monument Photo by

Dana Stubbs

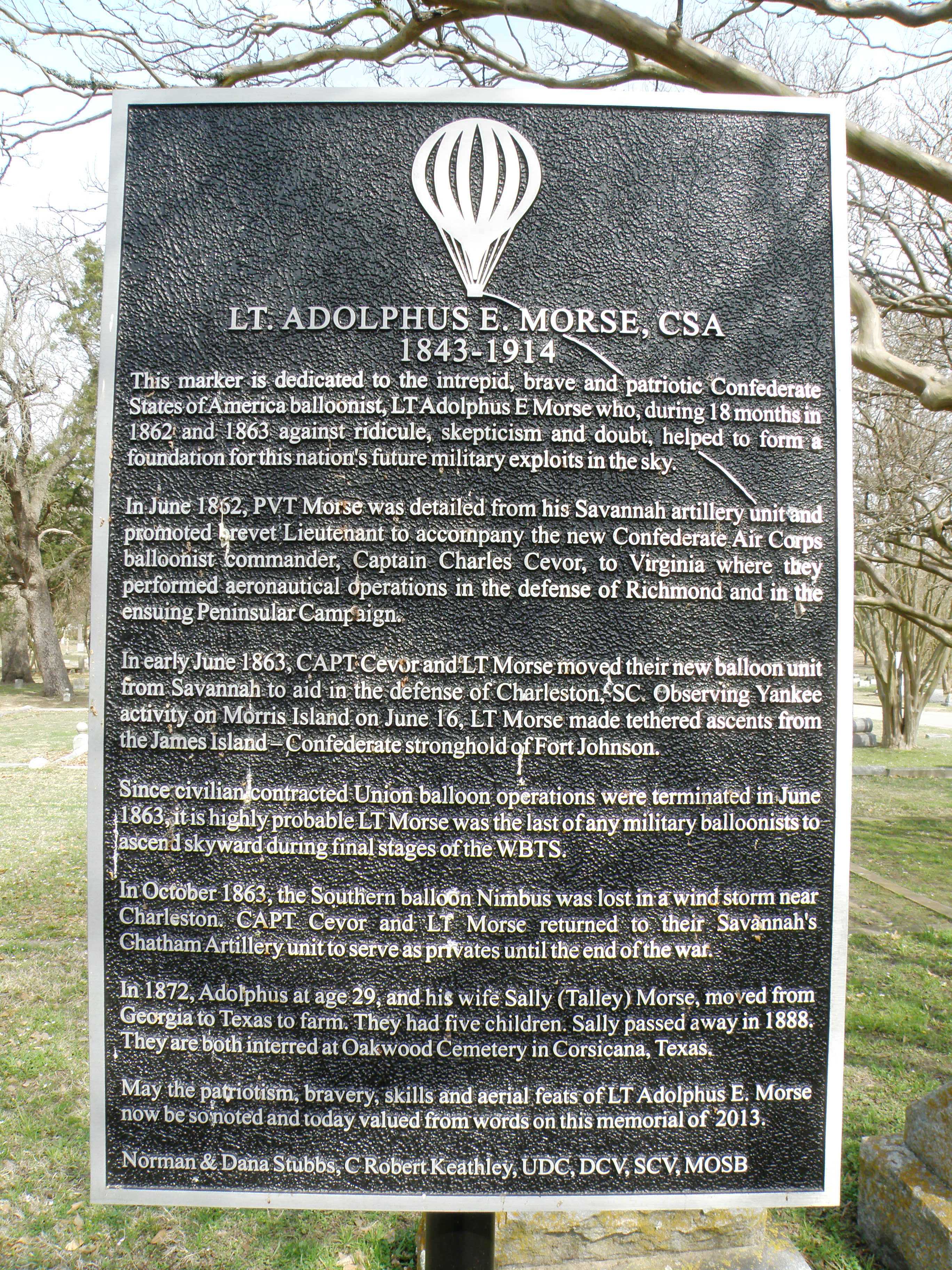

Courtesy photo The last reconnaissance pilot (aeronaut) to

fly in the American Civil War conflict, Adolphus E. Morse,

died in 1914 and is buried in

Oakwood Cemetery

in Corsicana. (OLD MARKER)

The Last Confederate Airman was a Texan

Corsicana Daily Sun

Corsicana — Introduction:

From the ranks of thousands in both Northern and Southern armies and their

balloon air corps, the last reconnaissance pilot (aeronaut) to fly in the

American Civil War conflict was Lt. A.E. Morse, C.S.A. He was born in Troy, Pa.,

resided 27 years in Georgia, and 42 years in Texas. Adolphus E. Morse died in

1914 and is buried in Oakwood Cemetery in Corsicana.

One 1910 criteria in determining qualifications for an applicant’s Texas

Confederate Veteran Pension was based on the 31st Texas Legislature and Texas

Commissioner of Pensions process so indicating a Confederate veteran must be a

bona fide Texas citizen having residing in the State prior to, and continuously

since, Jan. 1, 1880.

A.E. Morse came to Texas and became a farmer in 1872. He died in Texas at age

71.

By C. Robert Keathley;

Dana Stubbs, UDC-researcher

Corsicana Daily Sun, Corsicana, Texas

Special to the Daily Sun - May 30, 2010

Lost, Yet Found…The Last Confederate Airman

By C. Robert Keathley, Dana Stubbs UDC-researcher; © 2010

This is the first installment of a three-part series surrounding an amazing

piece of Civil War military history, which believe it or not, has ties to

Corsicana. Through the findings of researchers such as Keathley and Stubbs,

along with her husband, Norman, it appears there are several notable figures

from the Confederacy that made contributions to during the War Between the

States that found their final resting place here in Corsicana.

It began when Horace A. Morse placed pen on paper and expressed admiration for

his older brother Adolphus.

He was writing a personal testament about Adolphus as a soldier of the

Confederacy, and a grand transfer to a new military branch: The Air Corps of the

Confederacy.

The sincere feelings of Horace, through the 1910 written statements of his

memories and emotions, seemed ever present as they might have been back on a

fateful day in July, the 1861 day of his brother’s military enlistment, and

acceptance. Yes, back then thirteen-year-old Horace watched Adolphus don the

butternut greys of Savanna’s proudest, the historic Chatham Artillery Battery.

In and around Savannah it was well known: … “The Company always manifested a

choice in the selection of its membership, the following method was adopted. The

name of the applicant, who was vouched by at least two members of the Company

was brought forward at an assembly of the corps convened for that purpose. If he

received four-fifths of the votes cast, he was declared elected; otherwise he

was rejected. This rule presented the character of the Company, and acted as a

safeguard. The consequence was, that its members were always men of character

and reliability.” …1

The excited teenager now had a brother who was elected for battery duty as one

of Georgia’s high-spirited lads itching for a fight. Nearly five decades later,

Horace would tell of his brother’s military service, his character, loyalty and

his reliability.

Horace was now sixty-three years of age. Forty-five years since war’s end he was

to testify on behalf of his brother’s application quest for a Confederate

veterans state pension. Adolphus, age sixty-seven, was unemployed, without

property, a widower and nearly impoverished. Six dollars a month from Texas

seemed a bit paltry, but in 1910 and possibly a few years beyond, it would

surely help. 2

Horace wrote … “That for awhile he (Adolphus) was detailed and assigned to

special services with the engineer department, (and) was one of two parties in

charge of the Confederate Balloon – Captian C.C. Cevor being the other – and I

think received orders from Vice-President Alex H. Stevens – they being assigned

to the Virginia Department and resided in Richmond, Virginia. This however was

for a short time probably a year – when the said A.E. Morse returned to the

Artillery Company. (To cross interrogatories not already answered, witness

states that said A.E. Morse may have been on special detachment service

something more than a year, but the said H.A. Morse personally saw, was at the

making of, and was within the said balloon when the said Captain C.C. Cevor and

A.E. Morse had charge of it).” …3

In 1910, another former Chatham Artillery comrade-at-arms, Clement Saussey, now

age sixty-six, also wrote in behalf of Morse’s pension application: … “Morse was

detailed for some time. I do not know how long, as an assistant to Charles Cevat

(Cevor) – balloonist – He returned to the battery and was at the Surrender April

25, 1865.” … 4

Around the same time of the 1843 birth of Adolphus to Alonzo and Elizabeth Morse

of Troy, Pennsylvania, a slowly rising hot-air balloon, the Forest City, carried

a 22-year-old adventurer out over Chatham County. 5

The aeronautic balloon skills of one Charles C. Cevor in Mid-19th Century

Chatham County were marvels for many to behold. 6

Cevor and his future-to-be-rebel co-pilot, (now a lad of Pennsylvanian birth,

who would enlist for war at age eighteen), were somehow destined to meet in

Georgia; both would someday float above the clash and turmoil of mass maneuvers

and bloody conflicts below.

We don’t know exactly how, when, or where Cevor and Morse met. On the drill

field of Fort Pulaski? Perhaps meeting somewhere on the Isle of Hope, or at the

tent-city encampment of Camp Claghorn? They might have met in the old Armory

Hall in Savannah where balloons were constructed and repaired, (an activity

which caught the eye and noted attention of Pvt. Morse). 7

They did meet and both found two things in common: they had a keen curiosity for

adventure, and to pioneer lighter-than-air flight for the military successes of

their cause. Soon Cevor and Morse, both enlisted Privates in the Chatham

Artillery, would find themselves promoted as brevet balloon officers in the Air

Corps of the Confederacy. 8

Charles Cevor was experienced and skilled in his little balloon. Shortly after

shots were fired at Fort Sumter, and North and South mass hostilities began,

Cevor volunteered his personal balloon and services to the Confederacy. His

initial efforts prematurely landed on deft ears or, they were unfavorable to the

prevailing views of skeptics in military command. 9

Private Morse was proud of his Chatham Artillery enlistment. For him it was a

privilege to be in such a heralded battery, its origins dating back to 1785.

[Note: The second oldest organized American Military unit, the Chatham Artillery

– 1785, and its forward lineage, can be traced to today’s 1st Battalion, 118th

Artillery of Georgia’s U.S. Army National Guard.] 10

While Cevor stewed and paced in Savannah, his repeated appeals to Richmond were

rebuffed or unanswered. Pvt. Morse marched off to war and to battery duty at

Fort Pulaski. (He was latter reassigned with a segment of his battery to James

Island near Charleston, S.C.).

Meanwhile in April 1862, General Joseph Johnson, Commander of the Army of

Northern Virginia, became aware of Yankee balloon activity over Virginia.

Johnson made it know he too wanted balloon reconnaissance reports for the South.

So, and order was issued to Johnson’s adjutant, General John Magruder. A staff

officer to Magruder, twenty-one year old Captain John Alexander Bryant, soon had

Gen. Johnson’s orders on his desk for a special reconnaissance mission.

Impulsive ideas of glory, adventure, and opportunity for recognition led Bryant

to boldly volunteer for the mission. Captain Bryant went directly to General

Johnson with a plea to lead this mission. Little in advance did Bryant know that

this particular reconnaissance was not to mount on a good horse and ride, but

for an ascent above Virginia in a balloon.

After being informed of balloon reconnaissance, Bryant expressed strong

reluctance and resistance to go.

Bryant even indicated he had never seen an aerial balloon. 11

General Johnson sternly ordered Capt. Bryant to go courageously and become the

first military man to fly for the Confederacy. Johnson’s orders were followed

precisely. After a few successful ascents Bryant eventually lost his balloon to

a turbulent high-wind accident. Captain Bryant gladly returned to adjutant duty

never to fly again. 12

Part 2 of this amazing piece of Civil War history will appear in the May 27,

2010 edition of the Navarro County Times.

[Bibliography & Notes]

1. Historical sketch of the Chatham Artillery during the Confederate Struggle

for Independence, Charles C. Jones, Jr., 2005, Scholarly Publishing Office,

University of Michigan Library, ISBN-10: 1425521694, page 47.

2. Soldier’s Application for Pension (Texas), #17601, A.E. Morse, page 2,

#2-lines 10-15, Item #7; page 3-Item #15.

3. Ibid., page 13-14, H.A. Morse – answer to Interrogatory 7.

4. Ibid., page 7, Clement Saussey – 7th Interrogatory.

5. The War of the Aeronauts: The History of Ballooning in the Civil War, Charles

M. Evans, Stackpole Books, 2002, ISBN-10:0811713954; page 204, para 4.

6. Collections of the History of Albany, vol. 1, page 463, September 27th, 1859.

The Savannah Republic (newspaper), page 2, column 3, December 27, 1860. December

28, 1860, page 2, column 1.

7. Reminiscences of the Boys in Grey 1861-1865, Mary Yeary, 1912, Smith & Lamar

Pub., Dallas, Vol II, page 546, para 4, line 10… “I remember to have seen him

work on it…”.

8. Historical Sketch of the Chatham Artillery, C. Jones, p. 104

9. The War of the Aeronauts, Evans, page 205, para 5.

10. http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/agency/army/1-118fa.html

11. The War of the Areonauts, Evans, page 194-201.

12. Ibid., page 201, para 9, line 1-7.

Lost, Yet Found…The Last Confederate

Airman, Part 2

By C. Robert Keathley, Dana Stubbs UDC-researcher; © 2010

This is the second installment of a three-part series surrounding an amazing

piece of Civil War military history, which believe it or not, has ties to

Corsicana. Through the findings of researchers such as Keathley and Stubbs,

along with her husband, Norman, it appears there are several notable figures

from the Confederacy that made contributions to during the War Between the

States that found their final resting place here in Corsicana.

During the same April 1862, Brigadier General Thomas F. Drayton of South

Carolina, issued an alert to his chief engineer officer in Charleston, Captain

Langdon Cheves.

Cheves was ordered to post haste locate an experienced balloonist. Fortunately,

Captain Cheves had prior knowledge of the peacetime aerial exploits of the

Savannah aeronaut Charles Cevor. 13

Cheves contacted Cevor and within a short time both men began purchasing bolts

of silk throughout merchant houses in Charleston and Savannah. Cheves also gave

specific orders to Cevor. Not only should Cevor plan and build a new and larger

balloon in Savanna’s Chatham Armory but, to build a balloon large enough to

accommodate three military observers, their gear and ballast. 14

In April 1862, now (brevet) Captain Charles Cevor journeyed from Savannah to

Charleston on a personal mission. Arriving in a driving rain Cevor went to James

Island to confer with Chatham Artillery Commander, Captain John Wheaton, and

with Capt. Wheaton’s 1st Battery Section Leader, Lt. Thomas A. Askew. Cevor

needed a trustworthy

and reliable assistant and six enlisted volunteers for special assignment to a

new balloon unit, the Air Corps of the Confederacy. 15

A reliable artilleryman was selected. Nineteen-year-old Pvt. Adolphus E. Morse

was chosen and assigned to temporary balloon duty (a duty leading to eighteen

months in the air corps). Capt. Cevor not only accepted Morse as his assistant,

Pvt. Morse was promoted to the temporary rank of (brevet) 1st Lieutenant. Lt.

Morse and six artillery volunteers, without balloon, would commence new training

while lodged in amicable surroundings of the Charleston Hotel. 16

Meanwhile arriving by sea, a large Union army under the command of General

George McClellan landed on the Atlantic coast of Virginia and moved up the

peninsula toward Richmond. Confederate aerial reconnaissance was in dire need.

The new multi-colored vertically striped Savannah balloon, the Gazelle and its

crew were ordered to Richmond. After numerous delays and detours, the

Confederate Air Corps (one balloon, two officers and six crew), arrived ready to

fly on June 24, 1862. 17

General Robert E. Lee decided an experienced signals officer, Lt. Colonel Edward

Porter Alexander, needed to take full command of the Balloon Corps. After

numerous ascents by Lt. Col. Alexander, Capt. Cevor and Lt. Morse during the

Seven Day’s Battle in front of Richmond and reconnaissance from June 27th to

July 4th, the Gazelle and crew were transported down the James River by an armed

tugboat, the CSS Teaser. The Gazelle ascended and McClellan’s forces were

located. However, early on the evening of July 4th, a Union gunboat, the

Maratanza, prowling on the James River, captured the Teaser and its aeronautical

cargo. CSS Teaser personnel, Confederate balloon officers and crew, all avoided

capture and made their way back to Richmond. 18

Forty-seven years later, Morse would recollect in his pension application: … “On

the 4th of July we were ordered to go with the balloon down the James River to

try and find him (McClellan). We took the balloon on board the tugboat “Teaser”

and started down the river, and went about twenty miles down made ascensions and

found his army down between the Chickahominy and James Rivers. But, owing to the

obstinacy of the boats captain, he ran aground, and the enemy got our boat and

the balloon. Ourselves and the crew escaped and returned to Richmond, where we

were ordered to return to Savannah and build a new one.

We bought every yard of silk we could find in Richmond, Savannah and Charleston,

which was 1,000 yards. We remained with the second balloon in Charleston and

made observations from decks of vessels to ascertain their positions on Morris

Island and the location and number of their gunboats.” … 19

The Yankees cut the prized Gazelle into little pieces and sent them to members

of Congress in Washington, D.C. (Note: two silk items from the Gazelle, one of

13×34 inches, and another – 13×13 ½ inches, considered war booty, are in

protective custody located in the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum’s District of

Columbia facility). 20 The July 1862 demise of the Gazelle was certainly not the

end of the Confederate Air Corps and its aerial forays. In July 1863, Lt. Morse

would ascend to observe the location and status of Union army and navy activity

below in South Carolina. 21

On returning to Savannah, Air Corps officers and crew commenced work on a second

Georgia balloon (or the third balloon placed in service by the Confederacy).

The second balloon would not see service in either Georgia or Virginia.

The finale of this amazing piece of Civil War history, and interviews with the

researchers, will appear in the June 3, 2010 edition of the Navarro County

Times.

(Bibliography and Notes for this week’s column are available in the online

edition, available beginning Monday, May 31, 2010 at www.navarrocountytimes.com.)

Notes:

|