|

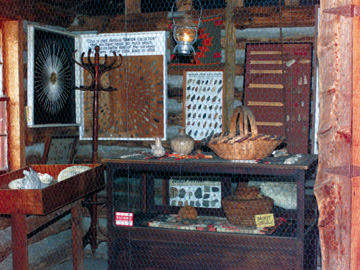

This log trading post was built by Dr. George Washington Hill in 1838 near the present Indian Spring, close to the Spring Hill community, on direction by General Sam Houston to promote better relations with the Indians in the general Navarro County region. Tribes active in the area were the Kichai and Yscani, of the general Wichita Confederacy, the Tehuacanas, and the Wacos to the south on the Brazos. Parties of Comanches and Kiowas from the plains, and occasional groups of Cherokees and Kickapoos from Oklahoma Indian Territory, periodically traversed or penetrated the region as well. Collections housed in the cabin include Cretaceous fossils and late Pleistocene paleontological finds, including a Mammoth tooth; Indian artifacts from the Archaic Period (8,000 to 2,000 years ago) on up through the Historic, including in the latter many arrow points from the Surveyors Massacre battle site of 1838; and pictures and memorabilia of the famous Cynthia Ann Parker historic episode. The building was given to the Navarro County Historical Society in 1962 by Ott Matthews, a descendant of Dr. Hill. 7/1/2002 Indian Trading Post at Pioneer Village long on Native artifacts By RUTH THOMPSON/Daily Sun Staff

The Indian trading post was reconstructed with the logs from Dr. George Washington Hill's home (1838) that was built by Spring Hill and T.F. Larkin ranch that was located in Navarro Mills. Dr. Hill was appointed by president Sam Houston to promote better relations with the local Indians in the area which is now Navarro County. The Tribes active in the area were the Kichai and Yscani, of the general Wichita Confederacy, the Techuacans, the Wacos to the south of the Brazos, parties of Comanches and Kiowas from the plains, and occasional groups of Cherokees and Kickapoos form the Oklahoma Indian Territory, that periodically traveled the region as well. The cabin is filled with pictures and memorabilia of Cynthia Parker and reproduced photographs of the great Chiefs of the time period. There are many artifacts housed in this cabin all relating back to the Native Americans. The collections in Indian artifacts from the Archaic period (8,000 to 2,000 years ago) to the almost present time (late 1800s). The cabin even houses arrow points from the Surveyors Massacre battle in 1838. Also displayed are several pictures of several memorials, Dr. Hill's home and Dr. Hill. The walls inside the building are filled with sketches and photographs of famous Native Americans such as the local chiefs and the Parker family. The Indian Trading Post is the perfect exhibit of Native of American history in Navarro County with pictures for children and example of life back then for the adults. Ruth Thompson may be contacted via e-mail at [email protected] Dedicatory

Address of the George W. Hill Trading Post The June 3, 1962 Dedicatory Address of the George W. Hill Trading Post in the Pioneer Village in the Corsicana, Texas City Park, by Theo. S. Daniel, of Athens, chairman of the Henderson County Historical Survey Committee, and member of the Navarro County Historical Society. Although the introduction by my esteemed friend, the Honorable Mayor Bob Reading has indicated some of my linkage to Navarro County history, it appears to be another case of "Carrying coals to newcastle" for me to presume to address the Navarro County Historical Society concerning the George Hill Trading Post. However, even for you of the audience who are well-informed on the subject, I have a perspective to share with you that may deepen your appreciation of the true historical significance of the small log building that we dedicate today. Frankly, when your Society secured and dedicated the 1842 Ethan Melton original log building, I was amazed that one of our very earliest structures in Navarro County had withstood the ravages of elements and man to this date. Now you cap the climax, and I have one word to express my feelings --- AWE. For you not only have come up with an 1838 building, but you have brought to the Pioneer Village in Corsicana the very first structure erected by white man in Navarro County! This is remarkable in itself. Visualize for a moment the situation in Navarro County in 1838. To the South on May 19, 1836, Fort Parker had been destroyed, the defenders massacred, and Cynthia Ann Carried away and adopted by the Indians. Also two years before, the Alamo had fallen to Santa Anna, followed by the Texas Army triumph at San Jacinto. Then in 1838, Sam Houston, President of the Republic of Texas, appointed Dr. George W. Hill of Robertson County, Indian agent for the territory of which Navarro County was a part. In this area between the Trinity and Brazos Rivers was no white settler -- only the Indians. Most of these were courageous, intelligent Indians who preferred peace with the white man, but who often decided to fight to the death to prevent their lush buffalo land from being overrun and taken from them by these white intruders. In this atmosphere, Dr. Hill built his log Indian Trading Post at Spring Hill in Navarro County. In October of that same year and near his building, a party of surveyors came from Franklin, Texas and started making the first survey in the area. They were received in friendly fashion by about three hundred Kickapoo Indians and their families from Arkansas who were camped at the springs while hunting and preparing their winter's supply of Buffalo meat. When the purpose of the surveyor's work was learned, the Indians attempted to dissuade the surveyors from pursing their work in that locality by several harmless ruses. Upon failing by peaceful means to prevent this inroad into their hunting grounds and way-of-life, they attacked the surveyor's on their way to their survey lines and thus developed the massacre on Battle Creek near the present town of Dawson. Dr. Hill, for whom Hill County was later named, returned to Franklin, married Mrs. Katherine Slaughter who had two daughters, and brought them to his Springhill home. One daughter married and had a daughter who married Will Matthews. They inherited the old home place where the Trading Post was located. Mrs. Matthews died at the birth of their first son, Ott Matthews, who is still living on the place. This year Mr. Matthews gave to Mr. Alva Taylor the logs from the original Trading Post to use in constructing this building on its present site. It is indeed fitting that this building, built by Dr. George Washington Hill, a member of Congress and Secretary of War from 1839 to 1842, and commissioned Indian Agent by President Sam Houston "to establish a trading post and create friendly relations with the Indian tribes," should now house exhibits of Indian artifacts. Permit me to lend you my personal yardstick by which I evaluate the historical value of this Trading Post. The hound-run on which this microphone and I are presently situated is part of an original log house erected in Chatfield in 1854 for Dr. Cooksey. As an inducement to Dr. Cooksey to settle in Chatfield, our own Louis Hodge's father, Robert L. Hodge (cousin Dink to my family) sent his slaves over to help build this very house. At that time, my great-grandfather, Capt. A. G. Hervey, and Mr. Hodge were partners in a mercantile business in Chatfield and their slaves hewed many of these logs. Capt. Hervey (whose wife was Dink's first cousin) had only arrived from Tennessee at Chatfield on December 11, 1852 himself. Also in 1854 a house of similar design was being constructed in the south east part of the County by another great-granddad of mine, "Squire" Josiah Daniel, just arrived from Alabama. This log house is also still standing in a good state of repair. And only four years previously, the first of any of my ancestors arrived in Navarro County when old thee Daniel, my great, great, grandfather came to examine this country and do some surveying while he stayed with Rush Walker on Walker's Prairie North of the present town of Kerens. It was five years later that his son Josiah, also a surveyor, surveyed his land with Indians watching from trees, and even still later when my Grandfather fished at his lake in the Trinity Bottoms with Indians watching him, I know this early history because these ancestors of both my Mother and Father were among the early settlers of Navarro County. Yet what strikes me is that sixteen years before this Cooksey house and twelve years before my first ancestors arrived here, George Hill had built his trading post! Therefore, the entire span of Navarro County history as it concerns its white residents is a total of one hundred twenty-four years. And here today we owe so much to Mr. Alva Taylor for securing these logs for us that constitute the exact beginning of this span of history. This type of endeavor is indeed commendable and should be continued by all of us, but in recapturing the earlier period of the white man let us not overlook another aspect of our Navarro County history. Prior to 1838 this Trinity-Brazos region was no vast, still, uninhabited land. Many populous tribes of Indian inhabited all sections of the "New World." At one time centuries before the westward march of the white man, more persons lived in the vicinity of St. Louis, Missouri than now live there. Just across the Trinity River in Henderson County, carved stone faces have been discovered that are accepted by archaeologists as being over eleven thousand years old. A human skeleton found near Midland, Texas is regarded as the best proof, so far, that man was in Texas over ten thousand years ago. Other parts of this so-called "New World" have revealed evidence to substantiate the belief that he was probably here thirty thousand years ago! Thus we open a wide door on the historical aspect of this country when we consider the Indians. Our one hundred twenty-four year-old history makes the white man appear as a presumptuous new comer. Pray let us all endeavor to preserve his record, but in doing so, not obliterate, neglect, or fail to appreciate the ancient American cultures!. See Also: 9/18/2005

Bill Young: Drills, perforators and punches at Pioneer Village |

The

Indian Trading Post is one of the many buildings found at Pioneer

Village, however it's the only building dedicated to Indians or

Native Americans of Navarro County.

The

Indian Trading Post is one of the many buildings found at Pioneer

Village, however it's the only building dedicated to Indians or

Native Americans of Navarro County.