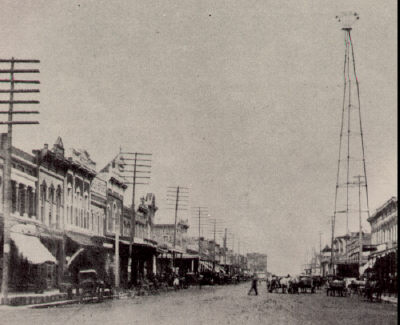

Under the Electric Light Tower |

Under the Electric Light Tower

The people who sold the tower to the City assured that the lights on top of the tower would illuminate the entire city with a radiance equal to a full moon. The tower was a triangular structure, similar to an oil derrick, but was much higher, nearly as tall as the present State National Bank building across the street. At the top was a circle of 20 brush arc lamps. These lamps did light up the immediate neighborhood, but dismally failed to shed any light a few blocks away. Bugs by the million flew to the lights, and often the streets and sidewalks under the tower were inches deep with dead bugs. While the tower was a failure in so far as lighting was concerned, it was a great talking point and a meeting place. "Meet me under the electric light tower" was a familiar admonition. So this paper, written at the request of Mr. Nelson Ross, to whom the writer has related many of the anecdotes which follow, is entitled "Under the Electric Light Tower." Parenthetically, Austin, Texas is the only other city I know of which erected electric light towers. Austin's towers were smaller, one-legged deals, and much lower than the giant in Corsicana. A few of Austin's towers are still in use. It has often puzzled folks as to just why an emigrant from any part of Europe came to Corsicana, Ennis, Dallas or any other locality. The only person I know who gave valid reason for locating in Corsicana, after leaving his native land - Poland - was Jacob Salinger. Salinger, from his violent gesticulations and stertorous way of talking was promptly dubbed "Crazy Jake" by Corsicana. Salinger said the reason he came to Corsicana was because when he landed at Ellis Island he had no particular place in the promised land selected. So, an interpreter took him to a railroad station. There, his money was counted, a five dollar bill wag given him to keep for eating money, and the rest was given to the ticket agent. The agent shuffled through his folders and books, then he went to work on a ticket five feet long. Salinger says he was put on the train, and then on one train after another, until he reached Corsicana, where the conductor kicked him off. Salinger prospered here, and later moved to Tyler. Ribe Freedman, a pioneer merchant here and long time chief of the fire department, told me when the news reached Corsicana in 1884 that Grover Cleveland had been elected as the first Democratic president since "before the War," it caused great jubilation among all the citizenry which had been oppressed by Republican reconstruction for so many years. Plans were made for a gala celebration the following Saturday night. Hugh piles of wood and trash were erected in every intersection of Beaton Street from Confederate Avenue (now Seventh Avenue) to Lee Avenue (now Third Avenue), for bon fires. Torch light parades were to be held, and good Democratic oratory was to be had. And naturally, some invite "John Barley" corn to join the festivities. Joe Strupper was then chief of the fire department. He feared the celebration might get out of hand, and the entire city burn down. Accordingly he deployed his equipment and detailed firemen to patrol Beaton Street while the bonfires were lighted. When Captain Garitty, president of the First National Bank, heard of Strupper's plans, he heartily approved and sent word to Strupper to be sure and detail good Republican firemen to guard the block in which the bank was located, because Democratic firemen might help celebrate, but Republicans would not since they were dour over loss of the election. One of the great characters of the early days was Pietro "Pete" Bisso. The main building of the Twilight home now and before the erection of Memorial Hospital, the site of the County Hospital, was built by Bisso for his home. Bisso operated a saloon on the corner now occupied by Buie's and back of this, toward the railroad tracks, where Buie's yard is, he operated one of the first soda water plants, "The Lone Star Bottling Works." The Lone Star, by various means transfers, operates today as the Dr. Pepper plant. Bisso was a short, round Italian whose English speech was a delight. There are many anecdotes about him, of which I will relate a few. He had a great enmity against an early day railroad man named McCalanahan. One day a stranger came in Bisso's saloon and asked him if he know McClanahan. Bisso put his hands on his ample hips and looked up at the man and asked, "Sometime he brakeman?" The man replied "Yes." Bisso then asked "sometime he conductor?", Again the answer was yes. Then Bisso asked, "Sometime he yardmaster?" Again yes. Then Bisso came out "All the time he a #### #### ####? The man said yes. Bisso said "I know him." Perhaps Bisso had good reason not to like McClanahan. In those days it was legal for bar rooms to stay open until noon on Sundays (and after noon when the front door was closed and the shades drawn, the back door was generally open). McClanahan had the habit of visiting a barroom Sunday morning, buying a drink or two, then tendering a $100 bill in payment. The barrooms could not make change, so Mac got free drinks. Bisso gave this matter much thought and like his compatriot, Machiavelli, came out with a great scheme. He got $100 in nickels, dumped them loose in a small canvas sack, and sat back to wait. Sure enough, on a soon Sunday morning in walked McClanahan. Ordering a drink or two, he made the offer of the $100 bill. To his consternation, Bisso took the bill and reached in the safe for the bag of nickels. These he dumped loose on top of the bar. He then counted out the dollar or two that McClanahan owed him, and said, "You gotta your change," and he refused to give up the sack, so McClanahan had to fill his pockets and hat with his huge store of nickels. Another early day bottling plant was the "Corsicana Manufacturing and Bottling Works (now the Coca Cola plant), managed by "Dr.." Harris E. Kinsloe. The "doctor" went with the business, as Dr. Pepper. Kinsloe bottled a drink named Dr. Kinsloe. Kinsloe was later on postmaster here, and is best remembered for "Kinsloe House" his home during his lifetime. Bottling works in early times manufactured their own syrups, generally three - lemon or white, strawberry or red, and cream or brown. They made their own carbonic gas from marble dust Ca oz and sulfuric acid H2 SO4. I leave it to the more erudite to make the equations. Crown caps had not been invented and the bottles were closed with rubber gaskets set in the bottles and hard rubber balls held against the gasket by gas pressure in the bottle, or by a wire hood which pulled a rubber gasket tight in the bottle. Gas was used at high pressure and bottles frequently exploded while filling and most bottlers had plenty of scars from flying broken glass. Likewise, it was hard to clean bottles as well, because of the cumbersome closing, so salicylic acid or benzoate of soda was used to deter spoilage. But I digress too much --- back to Bisso and Kinslow.... Mr. Kinsloe once told me he and Bisso were very active and aggressive competitors. About the only comity which existed was exchange of bottles and cases. One summer in the 1890's, Mr. Kinsloe said business was very bad, and getting worse. As a stimulant, Mr. Kinsloe decided to cut the price from 50 cents a case to 35 cents a case. A day or two later, related Mr. Kinsloe, Peter Bisso waddled into Kinsloe's office. Bisso came right to the point. "Harris,"he said, "They tella me you cutta the price to 35 cents." Kinsloe replied "Yes, Pete I did. Business is so bad I thought it might pick up." Bisso shook his head and replied, "Harris, I no like. Harris, you liva in a biga two story house." Kinsloe said he did not know what he was driving at, but had to say, "yes." "Harris, you gotta a man cut your grass, hitcha your horse, cleana the yard. Mrs. Kinsloe gotta a cook. You buy the good roast, good steak, all the besta to eat." Again Kinsloe had to agree, but was at a loss to what Bisso meant. Then Bisso delivered the punch blow. "Harris, I cutta my grass, my wife she cooka and washa the clothes. A nickla soupbone and a nickla macaroni feed us good, I harness my horse. Harris, I no like cut price, but you cut, I cut." Mr. Kinsloe told me he threw up his hands and said, "Pete, the price is 50 cents a case." Kinsloe said that Bisso could have - and wold have - starved him out. E. K. Howell of Kerens told me he was raised in Brown's Valley, where his father was a school trustee for the Montfort School. One summer the teacher quit and the board advertised for a new teacher. One Lewis P. Hodge was a young man, of slight build and a juvenile appearance. The board of trustees found his education all right, and thought he was capable of teaching the school, but they doubted his ability to maintain discipline. The board told him they had some tough boys, as large or larger than Mr. Hodge, and they feared he could not control them. Mr. Hodge said he could, so with misgivings, they hired him. Mr. Howell says when school started, the toughs decided they could do as they liked. they were wrong. Mr. Howell said in two days, Mr. Hodge had, by a combination of the puglistic ability of Jess Willard and J. J. Corbet, tamed all the hard cases, and had the best run school in all of Navarro County. Another of our characters was Upton Blair. One time locomotive engineer, he later was engineer and manager of the compress here. Too, he was manager of the "Oil City" baseball team when Corsicana was in the Texas League. Patent medicines and tobaccos were extensively advertised by placards pasted or tacked to any surface available. Old folks can remember when riding along the roads, seeing an endless series of placards extolling all sorts of remedies; Grover's Chill Tonic, Wintersmith's Chill Tonic, Mustang Liniment, Sloans' Liniment, Peruna, Pinkhams, and so on ad infinitum. Too, every brand of snuff, chewing and smoking tobacco decorated the trees and fence posts. In town, the signs were stuck anywhere there was space. One day, while Upton Blair sat in his office at the compress, a drug salesman stopped at the compress and started putting up his advertisements. Blair watched him work for a couple of hours until the man had the compress well covered. As the man started to leave, Blair walked out and accosted the man. "Got them all up?" he inquired. The man said, "Yes I have really done a good job." Blair then said, "Well, you can get busy now and take them all down." The hapless salesman protested and asked him why, if Blair did not want the signs up, had not stopped him when he started. Blair replied, "Why did you not ask before you started." So down came the signs. Navarro County has always had good lawyers and in the years many stories are told of their legal acumen. Joe Simkins is the authority for this one: Joe said around 1900 he was visiting in the office of another lawyer, W. J. Weaver, when in walked a well-dressed colored woman. She looked around and asked for Lawyer Weaver. Weaver identified himself and inquired how he might be of service. The woman said she wanted a divorce. Weaver pulled out a yellow scratch pad and stared getting the names, dates, and locations. The woman interrupted and asked how much it was going to cost. Joe said he gasped when Weaver said $50.00, since the then customary fee for a negro divorce was never more than $10.00. The woman said the fee was all right, and , turning around lifted her skirts and pulled a roll of money out of her stocking and counted off the $50.00. Here I might interpolate by saying many years ago, women's stockings were called the "First National Bank" and many banks had a "stocking room" where women customers might take money from their stockings to deposit, or place money they had withdrawn from the bank. Anyway, Weaver got all the pertinent information and told the woman to come back six weeks later and he would have her divorce. The woman walked to the door, turned back toward Weaver and said, "Lawyer Weaver, I forgot to tell you my husband is dead. Does that make any difference?" Joe says Weaver never bobbled, but answered, "It sure complicates matters, but I can handle it." Hawkins Scarborough, long time District Judge here, related the following story at a meeting of the Navarro County Bar Association. Since the meeting was a festive one, the tale may be taken as part of the give and take program, and is very possibly an embellished enlargement of facts. Related Hawk: "One morning when I came in the Court House I saw a good old colored man who lived on Briar Creek, a few miles north of Zion's Rest, walking up and down in the lobby. I spoke to him and asked, "What are you doing here, Uncle Isom?" The old negro replied he was a witness in the lawsuit which was then being tried. Hawk asked him, "Well, Uncle Isom, what do you know about this case?" The old negro replied, "I don't know, Judge McClellan ain't told me yet." The railroad (Houston and Texas Central) came to Corsicana in 1872. From there on until about 1900, while Corsicana was not a Dodge City or an Abilene, yet there were plenty of hard toughs around. Therefore, the City Marshal, to preserve order had to be a man like Wyatt Earp or others of frontier fame. One of these City Marshals was Ed O'Neal, the father of Mrs. Kirbe Steele. Katie Angus, a niece of the O'Neal's - Mrs. Alexander Angus and Mrs. O'Neal being sisters - told me the following story: During the 1890's when Ed O'Neal was City Marshal, there was a rash of horse-stealing. The marshal, the sheriff, and the constable, with all their deputies, were making diligent search for the thieves. One afternoon, Mrs. Angus, with her children, visited Mrs. O'Neal. There they decided to play a joke on the marshal. They tied the O'Neal buggy horse to the back of the Angus buggy and led the horse to the Angus home, which was located south of town, across the H. & T. C. railroad from where the Magnolia Refinery was later built. O'Neal came home to find his own horse missing. Naturally, he raged and stormed. When horse thieves stole the Marshall's horse that was going too far. The town and country was searched, but no horse was located. After several days, Mrs. Angus led the O'Neal horse home and the Marshall decided the thief had returned the horse because of the fear of hanging. And there Mrs. O'Neal and Mrs. Angus were happy to leave the matter. When the H. & T. C. railroad came to Corsicana in 1872, the General Manager was a man named Quinlan. He was, no doubt, a good railroad executive, but was a notoriously poor poker player. Legend had it that Quinlin's poor poker was the motivating cause of the division shops and roundhouse being moved to Ennis in the 1880's. The story goes that Quinlan, always a loser, got in a heavy poker game with some of the wealthy citizens in Corsicana one night. He lost very heavily and swore the Corsicana men had framed him and cheated him. Therefore, he pronounced "he would make grass grow on Beaton Street," and proceeded to move the railroad shops to Ennis. Another anecdote told about Quinlan goes as follows: Some passenger conductors felt any cash fares they collected belonged to them, because if the passengers wanted to pay the railroad they would buy tickets. Quinlan was riding the train to Corsicana when he observed the conductor collect and pocket a cash fare. He hailed the conductor and told him he was fired. When the train reached Corsicana the conductor asked Quinlan to get in his buggy with him, as he wished to show Quinlan something. The puzzled Quinlan got in the buggy and off they drove. Going up Beaton Street, the conductor pointed to a brick building and said, "this building is mine and all paid for." He then drove on and pointed out several other pieces of property he owned. Quinlan said, "You have made me feel better about firing you, since I see you will not suffer." The conductor replied, "You miss the point, Mr. Quinlan, the railroad paid for all this, and all I knock down is what you could call pocket money, but a new man would have to accumulate, so it is cheaper for the railroad to keep me." The H. & T. C. railroad was largely built by convicts leased from the State penitentiaries, since the State of Texas, for many years, followed the practice of renting prisoners to the best bidder. The free labor was paid with orders on the paymaster who was supposed to make payments once a month from a car hauled up and down the line in a regular train. Sometimes the railroad ran short of money and the pay car would not make its run for two or three months. The railroad workers who had to have money were forced to sell their time checks as best they could at discounts of from ten to fifty percent to merchants or monied people. When the railroad reached Sherman about 1875 and made connection with the M. K. & T., Corsicana and other points in Central Texas got their first ice service (in the summer). "Northern Lake Ice" was shipped in and sold for 5 cents a pound. This practice continued until Anheuser Busch built the ice factory on South 14th Street in 1892. This plant is still operating under the ownership of Southern Ice Company. Anheuser Busch was able to deliver ice to homes at 50 cents a hundred and at 35 cents a hundred in large lots against the $5.00 a hundred for ice shipped in from Illinois, Minnesota or Michigan. At the start of this paper, mention was made to Kiber and Cobb's restaurant and confectionery. A vagrant thought recalls one of their delicacies, the oyster loaf. They took a square loaf of bread, then called a Pullman loaf (now known as the sandwich loaf), sliced of the top, hollowed out the interior, toasted and buttered the interior, filled the cavity with a dozen fried oysters, garnished with lemon and pickle, replaced the top and delivered it around town for all of 40 cents. On the other hand, then ice cream cost a dollar and forty cents a gallon and well worth it, being a frozen custard -- twelve eggs to a gallon of half cream and half milk -- no filers or stretchers used. They sold but one cigar, "Trade Mark", for 5 cents each or six for a quarter. This cigar came in 4 or 5 shapes and tree degrees of strength - from mild to very strong. They averaged 10,000 to 15,000 sales of these cigars a month. Further down the block from the light tower and Kiber and Cobb's was the Merchant's Opera House, which occupied the space now used by Builders Supply Company and Buck's Appliance Store. The opera house was built in 1892 and served as the cultural center of Navarro County until it burned down in 1913. On the ground level there were located the post office, the Oak Hall or Opera house bar, Leverman's Paint Store, a barber shop, and the wide staircase which led to the "Commercial Club" office on the mezzanine floor. The Commercial Club was the then version of the Chamber of Commerce and some of its early managers were Rufus O. Elliott, father of among several children, Arthur G. Elliott, and J. B. Slade. The clubroom doubled as a ballroom and may fine dances were held there annually. The wide stair then went on tot he theatre proper. The theatre proper was of about 800 seating capacity, and was on a par in equipment and furnishings with any in the country. The management booked the same road attractions as did Dallas and Houston. To name a few of the shows presented in the theatre were Joseph Jefferson in "Rif Van Winkle"; Chauncey M. Alcott, Golden Voiced Al Wilson, Sisseretta Jones' "The Black Patti" Al G. Fields Minstrels, Lew Dockstader's Minstrels, Charles H. Yales' "Everlasting Devil's Auction," East Lynne, Ben Hur, plenty of Shakespeare - Macbeth, Taming of the Shrew, Romeo and Juliet just to name a few. Many of these attractions returned year after year, along with new dramas. So many of the actors became well known locally. Al G. Fields always went hunting with Charles Pisek who was a fine merchant tailor here. Others fished, and others put on private shows at the "Elks." The tariff for road shows was $1.50 for the best seats "the dress row," $1.00 for the "Bald Headed Row" as the tiers of seats closest to the stage were called and for the "Parquet" the seats to the back of the theatre. Balcony prices ranged from 75 cents for the best seats down to 25 cents for the "Peanut Gallery" where the Hoi Polloi sat. Then there were many repertoire companies -- the best known and liked that of Albert Taylor and his wife, Gertrude Lawrence -- who would stay for as long as two weeks and put on a different show each night for a price range of 10 cents to 30 cents. About 1902 the first motion pictures shown in Corsicana were at the Merchants Opera House. They were advertised as "Sheppards Great Novelty Moving Pictures." Of the several pictures shown I recall only "Edison's Great Train Robbery." The Opera House was used for many ancillary purposes. Many state political conventions were held there. Religious services, and until the theatre was burned down, the graduation ceremonies of the Corsicana High School were held at the Opera House. Churches and other groups used the Opera House to stage amateur performances, as well as hold conferences. The Opera House was not a great financial success. In the twenty-odd years of its life, there was only one dividend of 30% paid to the stockholders. But the dividends paid to the community in service to the community, in bringing cultural and dramatic art to the city made the opera house a great asset. Opera was never sung at the Merchants Opera House. The title "Opera House" was used to avoid the name of "Theatre." To many the theatre was regarded as evil. The theatre itself being a part of the devil's dominion, and all people connected with the theatre were classed as Satan's satraps. So, while it was moral to see the "opera" East Lynne, for example, it was sinful to see the melodrama "East Lynne." Light opera such as Gilbert and Sullivan's Pirates of Penzance," "Midado," and the rest were sung. And such comic operas as Aubers "Fra Diavolo" and others of the same sort were presented. The Opera House had a house orchestra, led by a professional musician and staffed by some professionally and some gifted local musicians. One of the leaders of the orchestra was Tony Cruz, a Spanish band leader on Admiral Cevera's flagship in the battle of Santiago Released as a prisoner of war at the end of the Spanish-American war, he drifted to Corsicana (another case of why, and no story like Jake Salinger's to account.) The Dallas "News" a few months ago had an account of Tony Cruz musical activity in Corsicana and the cities he lived in after leaving here. Some of the travelling theatrical companies carried their own orchestras, others a leader and a few "firsts" and augmented with the local orchestra. Occasionally, a concert band or orchestra would play from the stage, presenting, usually, a mixed program of popular standard and classical music, so as to reach all of their audience. Fiddling Bob Taylor and his brother, Alf, appeared on the stage. The Taylors had each been governor of Tennessee and later took to the stage -- separately -- giving a combination lecture, comical skit, mountain music and singing show. One time when Alf Taylor was here, a "gallery god" in the peanut gallery hollered, "louder, louder." Taylor stepped to the footlights held up his hand and declaimed, "On that last awful day, when the trump of doom has sounded, there will be some fool in the back screaming 'Louder, louder, Gabriel." The house kept quiet then. One of the oddest shows staged at the Opera House was that of Sam Nash around 1905. Nash, a native of Richland and a brother of Clay Nash, at that time was a traveling hypnotist. He hypnotized various subjects on the stage and had them go through various antics and, as the climax, hypnotized a man and put him onto a box such as the outer case of a burial casket. The man was then transported and buried in a six foot grave on a vacant lot on Beaton Street, along about where Golden Brothers Store is now located. Air vents and viewing ducts were attached to the box, an electric light suspended in one of them. Then the sidewalk barker invited the passersby to come in and see the man who was buried alive. Business was good at the macabre show. After four or five days the man was exhumed and carried back to the Opera House where he was taken out of the box and brought back to life, jumping about the stage telling how fine he felt. Following Sheppards moving picture show at the Opera House, there soon came the opening of several moving picture theatres. One of the first - I forget its name - was located about where Dyers or Clowes Floral is located. After several changes in ownership it was bought by M. L. Levine and by him christened the "Cozy." So, thereafter, to his friends, Mr. Levine was called "Cozy." From this small theatre grew Levine's "Ideal" theatre, where in addition to films several road show performances were had yearly for a long time. Another early moving picture theatre was the "Majestic" located on Collin Street where the Children's Shop is now located (112 West Collin Street). This theatre grew from a very mediocre start to Corsicana's first "plush" Picture show, with carpeted floor, pipe organ and all the rococo trimmings. Other picture shows were soon located, one on Beaton Street about where Woolworth's is now, one on South Beaton Street in one of the buildings now occupied by Buie's. This was the "Vendome." Another early show was located in the Daniels building, later the telephone building on the corner of Main Street and Fifth Avenue. All the early picture shows had loud blaring phonographs playing to attract attention from the passerby. Many had, as an added attraction "Illustrated Songs," These were stereopticon slides projected on the screen showing scenes illustrating verses of popular songs with the words shown too. A singer, Lee Van Nort is the only one I remember, accompanied by piano would sing the song. If the theatre-goers liked the song they would join in, especially in the chorus. The price of admission to these early moving picture shows was five cents. Naturally, the pictures were silent, and flickered at all times. The film frequently broke, stopping the show for several minutes until the operator could find the broken ends and splice them. These interruptions in the performance were always greeted by the audience with boos, cat calls and stomping of the feet. This sometimes aroused the ire of the operator who would angrily berate the audience, who would return the compliment with snide remarks about the competency of the hopeless operator. All of this added to the entertainment. Another early form of the moving picture show was the "Air Dome," merely a vacant lot with a high board fence on the sides, a screen at one end, and the admission gate and projection booth at the other. One of these was located across the street from the City Hall, where Penney's Auto Store now is, and another was on the Y.M.C.A. corner. In a way these air domes were fore-runners of the drive-in theatre of today. Until the Y.M.C.A. was built, this lot was quite an entertainment center. Skating rinks, air dome, revival meetings, and best from a cultural standpoint, Redpathe Chatauqua, which for a week each summer presented afternoon and night expositions of lectures, drama, music and other forms of edifying entertainment. A similar form of entertainment was presented in the winter under the name of "Lyceum." Until the Carnegie Library was built the Lyceum programs were given in various halls about the city. When the library was built, the Lyceum programs were held there. Up until about thirty years ago, no man considered himself well dressed unless he had his pocket knife on him. Boys from five years on had to have their picket knives. Knives ranged in price from 25 cents for a one bladed bone handled "Barlow" or a steel handled "Wardlow Steel" knife, and the two-bladed knife of the same make brought 50 cents. These knives were for boys and the less affluent adults. Better off men bought Rogers or IXL, the best Sheffield brands, or Henckel, Baker or Western, the best German knives. Boys used their knives to cut fishing poles, make "nigger shooters" handles (this was well before the days of Johnson who had decreed the name of catapult for this boyhood weapon). Boys (and girls too) played games with knives, the principal one being "Mumble Peg." Grown ups used their knives for a variety of purposes, practical and pastime. The main pastime was whittling. When two men met and talked they would each pull out his knife, pick up a bit of wood and start cutting away. Some men made a profession of whittling. Part of them were contemplative, sitting for hours, calmly and slowly reducing a piece of wood to a pile of thin shavings. Others were creative, patiently whittling for days, cutting out a chain with a movable ball cut out in a cage at one end of the chain, and an anchor or other ornament at the other. Some whittled out guns, dolls, jumping jacks, and other toys for children. It may be the use of cardboard boxes for shipping containers in place of the heavy white pine boxes used until about 40 years ago, cut off the supply of good whittling wood. Some whittlers specialized on telephone and electric light poles, which, prior to the present creosoted hard pine poles, were white or red cedar, both good whittling woods. A whittler, or several of them, would slice shavings from up and down the pole until it was reduced to such small size it had to be replaced. The utility companies finally resorted to wrapping the poles with sheet iron to repel the whittlers' attention. |

Around 1890, give or take a year or two either way, the

Around 1890, give or take a year or two either way, the